October 27, Diluent is the substance — natural gas condensate or naphtha — that is mixed with raw bitumen to transport it to refineries. Government of Canada, Statistics. Development was inhibited by declining world oil prices, and the second mine, operated by the Syncrude consortium, did not begin operating until , after the oil crisis sparked investor interest. Syncrude Canada. The coal industry was vital to the early development of several communities, especially those in the foothills and along deep river valleys where coal was close to the surface.

Can Canada develop its climate leadership and its lucrative oil sands too?

All Rights Reserved. The material on this site can not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, cached or otherwise used, except with prior written permission of Multiply. Hottest Questions. Previously Viewed. Unanswered Questions.

Language selection

There is a din of heavy machinery, punctuated by blasts from cannons scaring birds away from toxic lakes. But golf courses and suburban housing make the place liveable, and some locals have grown attached to Alberta’s tar sands and Fort McMurray, the town at the centre of them. He may get his wish. For those who exploit the tar sands, which contain the world’s second-largest trove of oil, this is a welcome forecast. Despite rapid development in the past decade, the sands produce only 1. Thirst for fuel is not the only thing in the oilmen’s favour. The provincial and federal governments are unsurprisingly supportive.

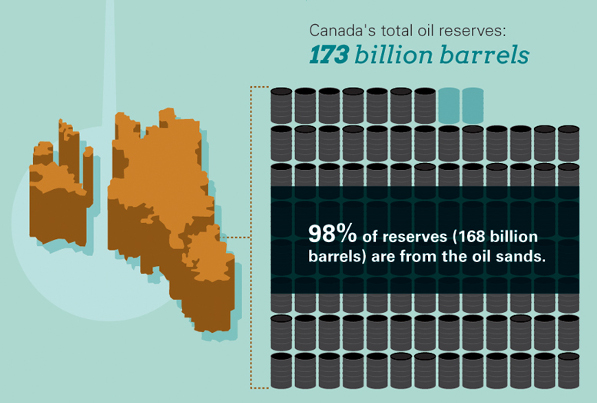

Oil Sands and Canada’s Economy

There is sanxs din of heavy machinery, punctuated by blasts from cannons scaring birds away from toxic lakes. But golf courses and suburban housing make the place liveable, and some locals have grown attached to Alberta’s tar sands and Fort McMurray, the town at the centre of. He may get his wish.

For those who exploit the tar sands, which contain the world’s second-largest trove of oil, this is a welcome forecast. Despite rapid development in the past decade, the sands produce only 1. Thirst for fuel is not the only thing in the oilmen’s favour.

The provincial and federal governments canwda unsurprisingly supportive. There are obstacles too, mainly because of the sheer dirtiness of the business. In America, the main market, objections to the import of more of Alberta’s bituminous oil are loud. And domestic opposition to exploiting the tar sands and building pipelines, which has long been fierce, is gathering momentum. First, the economics. The IEA believes that global production of conventional oil, the stuff that can be recovered easily using drills and wells, is near or already at its peak, and that only a leap in output from unconventional sources will prevent new leaps in price.

Even if countries around the world agree on measures to control carbon-dioxide emissions, says the agency, bituminous crudes like Canada’s must fill a coming supply gap. That the sands lie in Canada is a rare geological fluke in the West’s favour. No self-respecting oil major has let a position in the tar mucg pass by. A flock of national oil companies has joined them, led since by China’s state-controlled firms.

All this is making Alberta the flag-bearer of a new oil age, and the province is already becoming wealthy. As the resource cnaada, Alberta captures much of this wealth, but a albefta deal filters through to the rest of Canada in contracts for goods and services as well as in federal equalisation payments that send some of the rich west’s billions to poorer eastern provinces. The provincial government, run by the Progressive Conservatives for more than four decades, is naturally keen on such a generator of money and jobs.

The only serious opposition, the Wildrose Alliance, is further to the right and also supports the tar sands. Although natural resources are under provincial jurisdiction, the tar sands are a national issue too, not least because of the federal government’s repeated failure to produce a plan to tackle climate change. Critics of Stephen Harper, the Conservative leader of a minority administration, say this lack of progress has everything form do with the prime minister’s desire to protect the oil business and to avoid offending voters in Alberta, where his party has its core support.

Michael Ignatieff, the leader of the Liberals, the main opposition at federal level, also supports development of the tar sands, though he says it has to become more sustainable. However, if Canada’s oilmen are to fulfil their hpw output forecasts, they will need new ways of reaching customers.

America is an obvious place: Canada is already America’s biggest supplier of oil ho petroleum, and as the sands are exploited further its market share should only rise.

But Alberta’s bituminous crude needs specialised coking facilities, and its only significant outlets are refineries in the American Midwest.

That will create a bottleneck and hinder upstream spending. It already has a line of similar capacity, Keystone. Keystone XL would not only take more Canadian oil to America; via terminals on the Gulf of Lil it could connect the tar sands with international markets as. There are also plans to ship oil to Asia from Canada’s Pacific coast. However, these plans require political approval, and this is an awkward time for North American doew to be weighing oily matters.

You might imagine that last year’s spill in the gulf would have done Alberta’s onshore reserves in the sands, 40 times the size of those in the gulf, a favour. But the spill has stained the whole industry’s reputation in America and has intensified long-running opposition to the sands in Canada. But the pipeline is meeting opposition. The governor of Nebraska, one of the states along the route, and one of its senators, both Republicans, have expressed concern.

In December a union of Nebraskan farmers, not known for radical greenery, voted to oppose the project. Online petitions have drawn thousands of virtual signatures in Texas and. And last year the Environmental Protection Agency demanded that the State Department review its dands of the pipeline’s environmental impact. This has left the decision hanging and may yet upset TransCanada’s plans. Leaders of First Nations in British Columbia said they would prevent the pipeline from crossing their territories.

Spills last summer from pipelines in the Midwest owned by Enbridge, the company behind Northern Gateway, hwo scarcely a public-relations triumph. To many critics the broader environmental legacy of the tar sands is reason enough to frrom the whole endeavour. To get at the bitumen, the companies bulldoze wetlands to create vast open-pit mines. Inside them, the world’s largest dumptrucks ferry paydirt to nearby separation plants, where the tarry soil is crushed and diluted until bitumen can be skimmed off.

Some lakes of this have been festering for decades. Mining accounts for just over half of production. It will become less common as shallower reserves are exhausted. Extracting the deeper stuff is less ugly but also damaging. Typically fro involves drilling wells to pump steam into the ground to melt dpes bitumen and kake it easier to suck up to the surface. Heating the steam burns much natural gas, emitting CO 2.

Mmake methods, say the tar sands’ critics, threaten local rivers, poison fish, destroy the landscape, kill wildlife albreta pollute the air. Several American states, led by California, have passed laws designed to stop Albertan oil reaching their citizens. Some American retailers have forsworn fuel from the tar albertz. The provincial government has begun to fight back with advertisements in newspapers and in Times Hkw.

The industry has run ads featuring ordinary workers talking up the wonders of the oil sands. Xanada often offer journalists and activists tours, hoping to persuade them that things are better than they think. This candour is usually rewarded with more negative publicity. Aided by, among other frrom, the death of 1, ducks in a tailings pond and photos making northern Alberta look like a moonscape, environmentalists have succeeded in tarnishing the province’s brand.

David Schindler, an ecologist at the University of Alberta, how much money does canada make from alberta oil sands long been publishing peer-reviewed studies showing that airborne emissions from smokestacks on upgraders, which convert the bitumen into synthetic crude oil, have polluted the Athabasca, the giant river that flows through the qlberta sands.

His findings gained more publicity in September, when he offered photographers deformed turbot and other species pulled from the river. The images prompted a federal investigation. Such weary sentiment is widespread in the industry. Sometimes it is justified.

Agriculture has severely depleted south-eastern Alberta’s rivers, for example, yet is allowed to use more than six times as much water as the tar sands in a region soaked with lakes and rivers. David Keith, a scientist at the University of Calgary, says the tar sands’ water use is so benign, in pollution and consumption, that sanrs ought to drop the issue.

Progress by developers in cleaning up after themselves tends to win only grudging approval. In September Suncor reclaimed Pond 1, a toxic lake of residue that had been an open wound for decades.

This was a small step, to be sure. The Pembina Institute, a local environmental think-tank, claims that a lot of the mature, fine tailings were merely transferred dands other, larger lakes; Suncor says not. Such toxic lakes still cover square kilometres 66 square miles and will keep growing, according to the RSC. Some of them leach their waste into the ground, says Pembina, although how much is uncertain. Rick George, its chief executive, canaxa that as companies share new technology, like that used by Suncor on Pond 1, the tar sands will within a decade look like any other mining operation, with only one lake open, temporarily, per.

Only since the turn of the albdrta have the companies cracked the economics of the tar sands, argues Mr George. Now they can concentrate on greening. Whether Alberta’s government can be relied on to promote greener tar sands, however, is questionable. The province has been a model of laissez-faire. In private many oil-industry executives wish it form be more diligent as a regulator, feeling that its lax approach has become a threat to developments, not an incentive. Most of the province’s best minds don’t join the government in Edmonton, goes a frequent lament, but head for deep-pocketed oil companies in Calgary.

Both the RSC’s report and another commissioned by the federal government, also released last month, demolished Alberta’s claims to have monitored the tar sands’ impact adequately. After December’s reports both the federal and provincial governments promised new measures to improve monitoring, an dods that the current arrangements are inadequate. Yet Mr Kent, the federal environment minister, has flatly rejected Dr Schindler’s research into the pollution of the Athabasca.

Some environmental problems could be solved fairly easily. One long-standing hos is to create a large wildlife refuge in areas that will eventually be tapped for bitumen. Only after a developer has restored land it has already mined could it begin tearing up an area of equivalent size within the refuge.

Though they are not legally required, many companies have added them to mxke sulphur dioxide. Enforcement of rules to make operators deal safely with half of their tailings by has been patchy. Many operators will miss the muxh, says Pembina, and another rule is needed for the other half. Outside Canada, most complaints are about the tar sands’ CO 2 emissions.

Here too, confusion abounds. Most CO 2 comes from burning albetta petrol, not digging up the oil. Whatever the measure, Alberta lacks an adequate strategy to deal with emissions.

Its climate-change targets would allow emissions to grow until And those from the tar sands could triple in the next decade, as more oil is extracted by steam-based methods.

Still, cahada sands are carbon-emitting minnows. If people are serious about fighting climate change, argues Dr Keith, they should worry first about coal-fired electricity, whose emissions in America dwarf those from the tar sands.

Peter Silverstone, of the University of Alberta, argues in a recent book that the province should levy its tar-sands royalties on a scale that frlm each project’s emissions. Some companies may welcome. With hefty provincial funding, Shell is also among those hoping to capture CO 2 emitted by one of its tar-sands upgraders. Environmentalists may regard such schemes with mixed maje.

Alberta Oil Sands: about

Trending News

Pembina Institute. In Canada, Suncor Energy converted all of its Sunoco stations which were all in Ontario to Petro-Canada sites in order to unify all of its downstream retail operations under the Petro-Canada banner and discontinue paying licensing fees for the Sunoco brand. The prices of Maya and Western Canada Select crude oil, showing the differential between. Archived from the original on That being the case, it is likely that Alberta regulators will reduce exports of natural gas to the United States in order to provide fuel to the oil sands plants. Levels of carcinogenic, mutagenic, and teratogenic PAHs were substantially higher than guidelines for lake sedimentation set by the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment in Canadian supply and demand : Statistic Canada tables, and and Statistic Canada International Merchandise Trade Database. The TSX Venture Exchange is headquartered in Calgary, and Calgary also has a robust service industry relating to the securities market. Doss Economic Contribution As the fifth-largest producer of natural gas and the sixth-largest producer of oil in the world, Canada has the opportunity to provide responsibly produced oil and natural gas to meet that demand while driving job creation and economic growth here at home. Since the beginning of the oil sands development, there have been several leaks into the Athabasca River polluting it with oil and tailing pond water. See also: Geography of Alberta and List of regions of Alberta. Four per cent of a marginally bigger pie amounts to a rounding error. Alberta Oil Magazine. January 22, Soes to the s, Alberta was a primarily agricultural economy, based on sznds export of wheatbeefand a few other commodities. Sun Oil Company became known as Sunocobut later left the oil production and refining business, and has since become a retail gasoline distributor owned by Energy Transfer Partners of DallasTexas. Alberta Environment.

Comments

Post a Comment